I was reading a recent post on Bridging Differences about assessment, and in particular, testing. I respect Deborah Meier and Diane Ravitch greatly, and will take a short minute first to say that if you’re an educator and you don’t follow their epistolary-style blog, you really should. Anyway, the post is about testing and the need for data in schools. Deborah talks about how to address the “data problem” and how teachers can (and should) avoid turning their classrooms into testing settings.

I always read posts like these with only half-interest, I must admit. Why? Because I am philsophically opposed to standardized testing, particularly as it is used in American schools. Where I am from (Canada), standardized tests are linked directly to curriculum and used in an entirely different manner. I had no idea what US-style standardized tests were about until I moved overseas and began having conversations with my American colleagues. They later took on a whole new meaning for me when I had to write one myself: the GRE was required for applying to my top choice graduate schools. Ugh! I learned very quickly in my preparation that these kinds of standardized tests have nothing whatsoever to do with teaching and learning.

I’ve been lucky, I guess, that I’ve also never had to teach in a school where standardized testing has been emphasized. In Canada, my students wrote mandatory government exams in grades 3, 6, 9, and 12 (or 4, 7, and 10, and 12 in B.C.) — but again, these are always connected to the provincial curriculum. And my students wrote the Canadian Achievement Tests in grade 7, but schools never used this to “pin” teachers. In fact, such tests (in my experience) were never about the teachers at all. Schools I taught in used the CAT to help identify students who might need learning support, or a gifted & talented program. And such is the way international schools I have worked in have used standardized tests like the ITBS and the ISA.

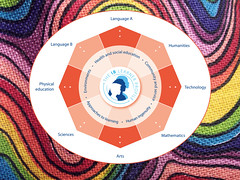

Internationally, I have only ever taught at MYP schools. And this comment, left on the Bridging Differences post I mention above, is one of the reasons why:

To get the kind of reliabillity that a multiple choice test delivers, the kids would have to spend a week to answer all the open-ended response questions, rather than the hour or two that the multiple choice test takes.

The writer of this comment, ceolaf (who leaves no URL with his/her comment), wrote a lengthy explanation as to why we need, whether we like them or not, some kind of standardized test because of the reliability issue. He further states:

The failure of THOSE tests that we hate does not in any way prove the superiority of our assessments. Our assessments have their own flaws.

I have two things to say in response to these two bits:

- I beg to differ. And,

- This is why I love MYP.