My mind is fresh from a weekend of intense PD with Jeff Utecht, who fervently shared his philosophy and expertise with me and my colleagues at UNIS Hanoi. It was, in all, a fast-paced but much needed weekend full of tips, tools, and tidbits to think about and implement. I am sure all of who attended Jeff’s sessions had some big take-aways from the weekend; one of the big ones for me was the concept of the community in the 21st century.

What role does the community play in education this century?

The answer, I think, is complicated. Jeff talked about how the community has to be built first, and how sometimes we as educators don’t get to choose where that community is — whether it’s Facebook, Twitter, SecondLife, or ClubPenguin. But I wonder: Don’t we as educators have a responsibility to create that community? Of course we should tap into communities already in place. But when it comes to the “New Learning Landscape“, I think teachers do have an embedded and non-negotiable responsibility to build the community with our students.

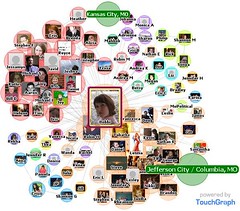

One of the challenges we face at UNIS is that our digital, online community is currently quite closed. While I have argued before that this is not always a bad thing, that the walled garden can be a great place to learn tools and play with ideas, I do think that there comes a time (particularly at the HS level) when the community must branch out. The fact that our students in grades 10 and 11 all have tablets (the first stage in our 1:1 roll-out) means that their community instantly was widened when they received their tablets. Having that tablet in their hands means they can reach out all the way across the world if they wish — they are connected. And why should we stop them? Not only does this new technology broaden their contact base and therefore extend their community, most of our students are third-culture kids who have lived in 4 other countries and are already part of an extended community outside our school doors.

If we are going to commit to the new literacies of the 21st century, we should enable our students to reach out to those communities, to find their authentic audience, and create their own learning environment. To deny them of this is irresponsible.

I’m grateful for Jeff’s ideas this past weekend and I think it is a great start for the journey with our students down the intertwined road of communities and literacy. Jeff got us thinking in the right direction, and armed with our wikis, blogs, Twitter accounts, and Nings, I daresay that our teachers and students are well on their way to embracing communities both within and beyond our doors.

And speaking of the community’s role in education, I happened across The KnowledgeWorks Foundation (courtesy of Lindsea, a member of my PLN and a contact of one of the KnowledgeWorks founders). The KWF is an educational philanthropic organization with some philosophical golden nuggets that make it stand out as an organization. The trademarked motto of KWF is “Empowering communities to improve education.” How fab is that? And if that’s not enough to get you browsing around their site, check out their Mission, Vision, and my favorite, their Values Statement:

Fanatical belief that all students have a right to a great education

Wow! Finding the KWF was a great way to end my weekend, and I look forward to seeing what their community initiatives in education will bring to education in the USA and elsewhere. You can also follow them on their Future of Ed blog.

All this excitement about communities, Web2.0, and literacy has made me very excited, but I’ve been so busy that the engagement has also made me rather ill — I have been fighting a nasty cold for about a week now. So as I sign off this post, tea in hand, I hope that my community of learners and colleagues will understand if I’m “below the fold” for the next little while, laying low while I recover.

Photo1 by ortica*

Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License

Photo2 by Librarian by Day

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License

Ongoing reflection task:

Ongoing reflection task: