[note: this was originally posted April 30, 2008 — back when I apparently used to blog more often. I’m resuscitating it as part of a #edublogBT meme begun by Jon Becker]

All this talk about writing, grade books, and “the unthinking habits of grading” has given me so much to think about. My mind is swimming.

The thing is, I think about this stuff all the time. It is only recently, after reading hoards of comments and postings (and all the bits in between) that I begin to understand my naivety. Or is it ignorance? (Hint: not everyone thinks about this stuff all the time.)

The thing is, I think about this stuff all the time. It is only recently, after reading hoards of comments and postings (and all the bits in between) that I begin to understand my naivety. Or is it ignorance? (Hint: not everyone thinks about this stuff all the time.)

First, a bit of background, for the sake of context

I grew up in Calgary, Alberta, Canada and attended Catholic, publicly funded schools. The teachers I had, with two notable exceptions1, all used criterion-referenced assessment to grade my work. I always (other than with the two notable exceptions) knew how I was being graded, even if they did average my scores and turn them into percentages. I graduated from an unusual work-at-your-own-pace high school in 1992.2

After completing an English Lit degree on the West coast, I entered Education. I did not realize at the time (1997) that the program I was in was progressive compared to most Ed programs out there. Thinking, ignorantly, that what I learned was what all teachers-to-be learned, I eagerly entered the world of K-12 education, armed with what I thought was Everything A Beginning Teacher Should Know.

One Epiphany (of many)

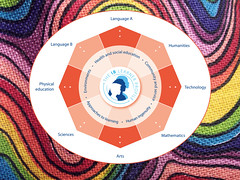

Fast-forward to 2001: I entered the realm of international education, working at an MYP school. Before this moment, what I knew about MYP could have filled an ant’s mouth. Sitting in an MYP training session, my then-mentor flashed the subject-specific criteria for Language A (MYP’s equivalent to English Language Arts) on a projector screen.

Thought #1: “Hey, that’s cool! That’s the same criteria my grade 7 teacher used to grade my writing, and it’s the same criteria I have always used to assess student work.”

[insert hmms and haws of other training participants here, as they ponder the criteria on the screen]

Thought #2: “Wait… doesn’t everyone use this?”

It wasn’t long after Thought #2 occurred that I learned the answer: No, not everyone is using this. Plenty of conversation and interaction with my then-colleagues (from various backgrounds in education, as expected in an international setting) taught me that what I had taken for granted my entire (short) life was indeed not “the norm.”

The Interim and a Confession

Over the past 7 years, plenty more colleagues, students, and their parents have shown me that other ways of assessing are indeed rife and plentiful. Just yesterday I engaged in three different conversations with three different families about this very topic (parent conferences were timely). Witness a verbatim quote from one of those discussions:

“Wow, this is so different from what we’re used to. You mean you want your students to come show you their work before they finish? You won’t take points off?”

[I won’t even get into the connotations implied by the use of the words “want”, “before”, and “points.”]

Don’t get me wrong — I do not think the same way about this issue as I did 10 or even 3 years ago. I have learned more than I can express on this small page about how to assess meaningfully. I have spent many, many teacher days fantasizing about not assessing at all, and like Dana Huff, I still have those days. I am guilty, in past years, of assigning my students the most boring five-paragraph essay you’ve ever read, just so I could be bored to death reading it and they could be bored to death writing it.

A Question … and Answers?

I have offered some of my thoughts about assessment before — indeed, the reason I initially began this blog was to reflect on what I was learning in an IBO PD course on MYP Objectives and Assessment. Now, having learned so much, I feel my philosophy of assessment is still evolving, and I do think long and hard about why I assess my students’ work and how I do it.

(And, please know that I mention MYP only because I feel it is one of the best educational systems out there for student learning. Is it the only one? No. Are there others that do the same? Yes. Is it just about best practice? Yes.)

So here’s the thing: I know there are other methods of assessment. I know about them well enough because I took the required courses in university, and I have seen them used in classrooms. But here’s what I still don’t understand — and please don’t mistake this for a rhetorical question:

Why are we still using them? (Do they facilitate learning?)

I’m starting, today, with just this question about criterion-referenced assessment, but know that I’m not limiting my thoughts to only this aspect of assessment. I anticipate that those thoughts — and more questions — will follow as my assessment philosophy further evolves.

Mid-evolution

So far, here is what I believe. Assessment is…

- primarily for learning; the assessment of learning is secondary.

- real and not “fabricated” just to put a number on a paper or in a box.

- goal-focused, and those goals should be based on where the students are at in their learning.

- varied, with a wide variety of opportunities given for students to reach their goals.

- frequent and woven into every aspect of what we do, while we are learning. (I am uncomfortable with the thought of students being either too excited or filled with dread at the mention of assessment; I want my students to see assessment as something we do all the time.)

- part of the natural learning process, not something tacked onto the end.

- not driven by reporting terms, boxes that need to be filled, administrative software, or any other nonsense that has nothing to do with the learner.

- applied when needed for learning, and not at calendar dates specified a year in advance.

1Okay, so really it was three notable exceptions. And they were notable because they were exceptionally bad teachers. I’m not naming names, it’s water under the bridge, yadda-yadda-yadda — and the truth is I learned many life lessons from these poor teachers.

2The dates are important, because I refuse to believe that the concept of criterion-referenced assessment is “new” and “progressive“. The dates, although applicable only to my personal experience and not bodies of research, further give credence to my personal belief that education is painfully, mind-bogglingly slow to change.

Photo Credits: Nice Hat by cwalkatron; Question mark by Leo Reynolds